The European Space Agency (ESA) has conducted a groundbreaking large-scale simulation demonstrating the catastrophic global impact of a solar storm comparable to the 1859 Carrington Event the most powerful geomagnetic storm ever recorded.

The test, carried out at ESA’s mission control center in Darmstadt, Germany, simulated an X45-class solar flare and its cascading effects on satellites, communications systems, and Earth’s infrastructure. Designed as a worst-case scenario, the exercise revealed how modern technology remains acutely vulnerable to space weather events of extreme magnitude.

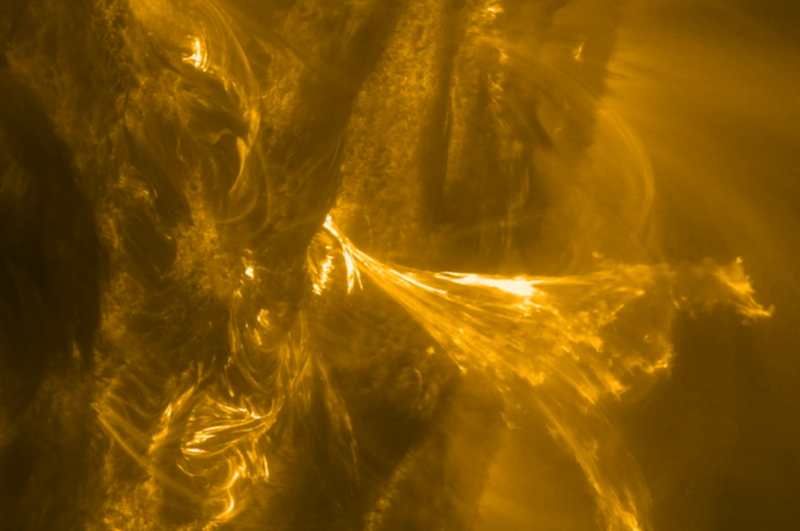

According to ESA scientists, such a storm would unfold in three devastating stages. Within eight minutes, radiation from the flare would disrupt communications, navigation signals, and radar systems worldwide. Twenty minutes later, a wave of high-energy particles including protons and electrons would strike orbiting satellites, destroying sensitive components and permanently disabling some systems. Finally, within 10 to 18 hours, a coronal mass ejection (CME) would slam into Earth’s magnetic field, triggering geomagnetic storms capable of overloading power grids, damaging transformers, and accelerating satellite orbital decay.

Thomas Ormston, ESA’s Deputy Spacecraft Operations Manager for the Sentinel-1D mission, described the potential consequences as unavoidable. “Should such an event occur, there are no good solutions,” he said. “The goal would be to keep the satellite safe and limit the damage as much as possible.”

The simulation also examined the Sentinel-1D Earth observation satellite, valued in the tens of millions of euros and scheduled for launch on November 4. Engineers admitted that shielding the satellite from a Carrington-scale event would be impossible.

Gustavo Baldo Carvalho, ESA’s Lead Simulation Officer, said the exercise tested every level of the agency’s preparedness. “Once the team regained composure, they knew a countdown had begun. In the next 10 to 18 hours, a coronal mass ejection would strike, and they had to brace for it,” he recounted.

ESA researchers warned that a similar real-world event today would cripple global communication networks and electrical systems. Satellite drag could rise by as much as 400 percent during the CME phase, increasing collision risks and shortening satellite lifespans.

“Satellites in low-Earth orbit are typically better protected, but an explosion of the magnitude of the Carrington Event would leave no spacecraft safe,” noted Jorge Amaya, ESA’s Space Weather Modelling Coordinator.

To counter future risks, ESA is advancing two key initiatives: the Distributed Space Weather Sensor System (D3S) a satellite network to monitor solar activity and the Vigil mission, planned for launch in 2031, which will observe the Sun from the Earth-Sun L5 point to provide earlier warnings.

The 1859 Carrington Event generated auroras visible as far south as Central America and caused telegraph fires in North America. A similar occurrence today would devastate global infrastructure, from satellites to power grids.

“It’s not a question of if this will happen but when,” Carvalho warned.

ESA officials said the simulation underscores the need for international preparedness against solar threats, noting that a near-miss in 2012 almost delivered a direct hit from a comparable storm.

The exercise follows a surge in solar activity earlier this year, when a geomagnetic event on May 11 produced vivid auroras over Finland a reminder, scientists say, of how close the world stands to another space-weather disaster.